On 12 July in Paris, the world’s largest restaurant will open ‒ a 3,500-seater facility designed to serve 15,000 athletes across 208 nationalities at any time of the day or night throughout the entirety of the Olympic and Paralympic Games. In total, across the two 15-day periods of competition, Paris 2024 expects to serve over 13 million meals: five million snacks for spectators; 3.5 million meals for staff and volunteers; 2.2 million for competitors; 1.8 million for the media; 350,000 hospitality meals, and 150,000 for the Olympic and Paralympic community.

What’s more, on top of the sheer volume of food to be distributed, the organizers have also committed to halving the carbon footprint of previous editions of the Games. When it comes to catering services, this means reducing animal proteins and offering more fruit, vegetables and plant-based proteins; limiting food waste; reducing the use of single-use plastics; and focusing on local and seasonal products to limit transport emissions.

Soaring expectations

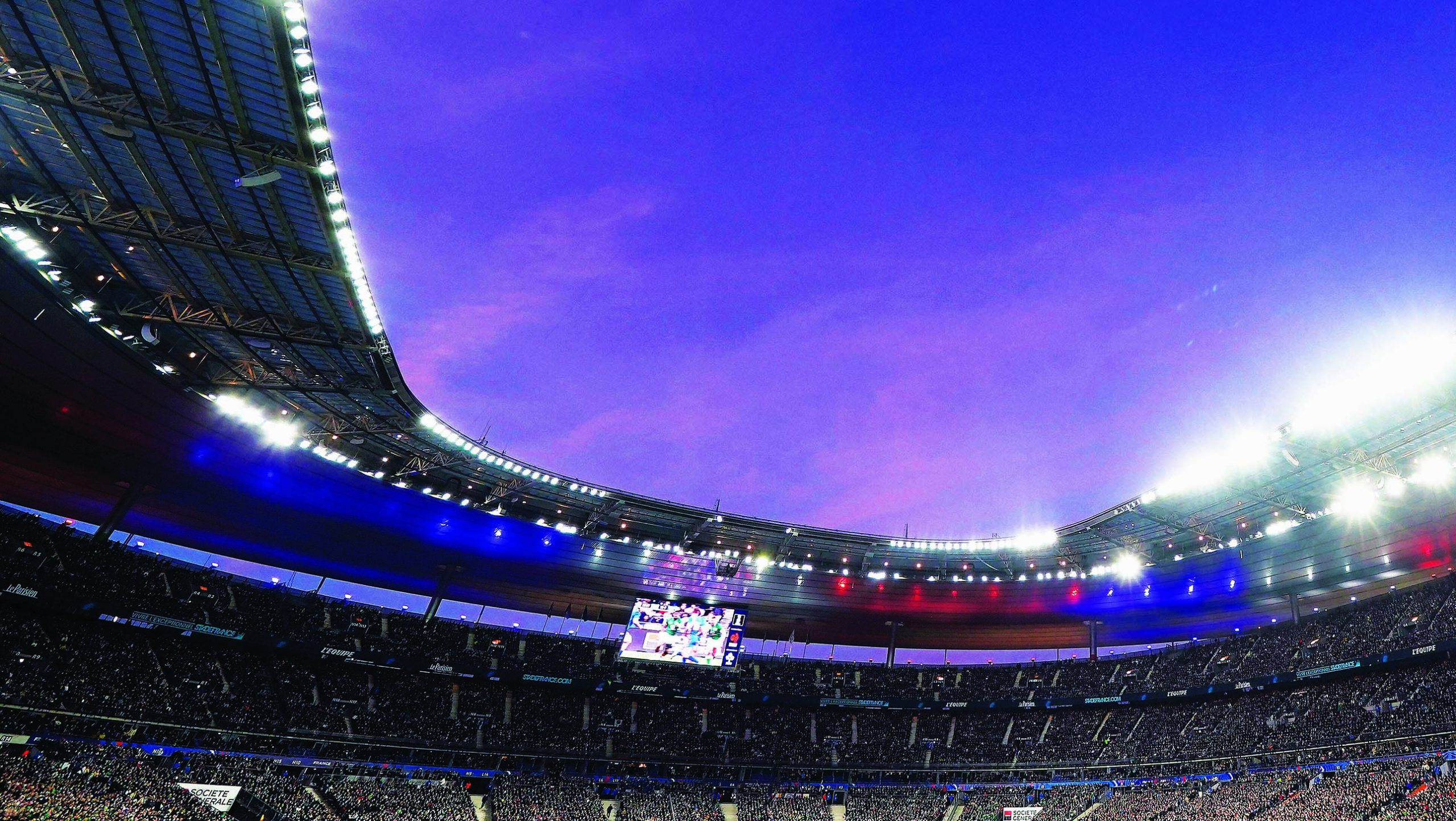

And Paris 2024 is just one of many sporting extravaganzas that will make up an action-packed summer of sport. Euro 2024 will place Germany’s football stadia in the spotlight, while the Cricket World Cup is held in the US for the first time. The mainstays on the global sporting circuit ‒ from Formula One to the World Series to Wimbledon to the Kentucky Derby – will all be returning to cater for thousands of hungry spectators, from the millionaires in the most expensive boxes all the way to the cheap seats. And expectations are soaring.

“Expectations of sports catering used to be right in the basement,” says Scott Heim, president of Ventless Solutions at foodservice cooking equipment manufacturer Middleby. “But not anymore. Gen Zs and Millennials are increasingly expecting the experience to be not just a spectacle of sport, they also want an elevated culinary experience. They don’t just want a hot dog; they want to come in and get sushi or a personal pizza or an Asian bowl, and those culinary demands are just going up.”

For the biggest and most high-profile events, like Paris 2024, variety is a must, according to Brazil-based consultant Armando Ricardo Pucci FCSI of Pucci & Associados. “Of course, it’s important to offer local dishes and local products, but when attendance is international, it’s crucial that people find their home reflected there. Organizers must start with the information about where the big delegations are coming and work from there.” With 40 different meals on offer every day based on four themes ‒ France, Asia, Africa-Caribbean, and world cuisine ‒ the Olympic and Paralympic Village in Paris, catered by Sodexo Live!, is setting a strong example for other operators to follow.

Something for everyone

Danny Potter FCSI, director of Invito Design in the UK, is a veteran of stadia projects and has worked on big arenas including the Millennium Stadium in Wales and the new stadium for Tottenham Hotspurs FC in London. His team is currently working on a large number of sports arena projects in the UK and Europe and several in the Middle East, including in the booming Saudi Arabia.

He says a stadium should have something for everyone. “A great example is where you’ve got everything from a coffee shop to a chicken shop to a burger bar, all the way up to Michelin-standard cooking,” he says, comparing it to a good hotel resort experience. “We have production kitchens that are bigger than most. We’ve got beer systems that deliver extortionate amounts of beer and a large amount of money. We’ve got bars, we’ve got cafes, we’ve got everything in there. It’s no different to a resort hotel, and 10 times more,” he says.

World cuisine may be in, but the classics ‒ think burgers, hot dogs and pizzas ‒ have certainly not gone out of style. “It’s more a question of ‘how can we do it better?’,” says Kristen Sedej FCSI, principal and owner of S20 Consultants, which has worked on more than 100 sports venues across the US. “Previously, a pizza stand in an arena might have hired out a third party to bring in, say, 50 pizzas, let them sit in a hot box and serve them from there. Now, they’re cooking them in front of you. It’s the same with burgers. Instead of cooking 100 burgers in a convection oven in a kitchen, wrapping them up and sending them up in hot boxes, you can actually watch someone make them right there.”

The increasing expectations from guests have pushed levels up. Potter says quality of product is the one big trend that stands out and refers to venue management company ASM global. “In the last four years they’ve gone on a big drive on quality. I started working with them four or five years ago and it was all frozen burgers; everything was precooked frozen,” he says. “Now they’ve developed their own burger and I would say this is probably one of the best burgers in a European stadium. It’s a completely fresh product.” This, of course, brings its own challenges. “How we cook it? Ideally on a plancha but we can’t be putting planchas into every single unit, so we do a lot of work with ventless for different venues.”

From dead spaces to pockets of revenue

And ventless technology is making much of this innovation possible. Traditionally, stadium operators have been limited as to where they can place their kitchens and cooking stations. Vertical, soaring ceilings, often three to four stories tall mean that setting up traditional ventilation systems is expensive anywhere except the perimeter of venues, where smoke, grease, and odors can be exhausted out of the walls. The typical set-up is a commissary kitchen in the bowels of the stadium, with cooked food being brought up and held before serving.

But new technology in the form of the ventless action stations developed by Evo, a division of Middleby, has begun to change the game, in the US at least. These easy-to-install set-ups use an ozone filtration system to remove fats, oils and grease from the airstream while also removing cooking odors. They can be set up anywhere in an arena with an electrical outlet and plumbing.

“This technology can help operators meet the demand for wider menu opportunities and higher food quality, and also give operators the chance to create pockets of revenues in areas that used to be dead spaces,” Heim explains. “You can place these stations by the escalator going up to corporate suites or right across from the bathroom, where fans naturally go during the break. It’s all about making it really easy for the fan to get back to their seat – but with food and beverage – and increasing the ROI of the space you’ve got available.”

They are quick and affordable to construct, install and move. “Think of all the costs associated with installing Type 1 hoods, metal flashing, support iron and compressors on the roof. Every vertical story adds £12k to £16k in Type hood flashing costs alone,” Heim explains. “And if personnel realize that the installation might be better placed elsewhere, the ventless portfolio is portable.”

Middleby has installed ventless cooking stations at over 70 arenas across the US and sees enormous opportunities in Europe and the Middle East. “Why would you hide one of the stars of the show ‒ the food ‒ in the bowels of the stadium when you can cook right in front of the fans and give them the sights, sounds, sizzle and aromas that add to that experience?” Heim says.

Higher quality, more pOS

For Sedej, ventless cooking stations are an important innovation helping her arena catering clients elevate their food offer. When designing a stadium F&B set-up, she often combines these with ‘frictionless markets’ where fans can grab bottled beverages and pre-packaged food items, and checkout either at a manned POS station, a self-checkout or, if they’re pre-registered, they simply walk out and technology automatically charges their credit card. “As the cost for this technology has come down and the infrastructure requirements have become smaller, I’ve seen frictionless technology and self check-out really permeate the sports market in the US,” she says. “Operators are recognizing that they are seeing an uptick both in their per capita sales and customer satisfaction.

“What we’re trying to do is come at it from both angles. We’re paring back the cooked food offer and focusing on what can be done really well, but at the same time introducing more points of sale. In the last 20 years that I’ve been doing this, I’ve seen a gradual shift; over time, the number of points of sale has probably doubled.”

Some operators are dividing their facilities up into quadrants to ensure fans can be served more quickly. In some situations, this will mean four carbon copy F&B offers. “The idea is that things are evenly distributed so that you don’t have to leave your seat for very long ‒ you can just grab something and come back.” In other settings, where there is a mix of premium and general seats, each quad will look slightly different. “Operators need to look at the number and type of seats that are being serviced, analyze those metrics holistically and map out where people are sitting and what their patterns are, to make spaces as efficient as possible.”

In premium areas, Sedej is seeing a move away from self-contained suites to more communal areas, as well as bringing kitchens closer to guests. “Instead of just ordering once for the whole game, suite holders can add extra orders on demand. The traditional big spread is not going to go away, but it’s being supplemented more now with an a la carte offer too.”

Bringing stadia alive outside game times

Every sports arena’s calendar is different, but as a rule they won’t be serving food and drink to sports fans every day of the year. Reducing wastage is becoming a greater focus for stadia foodservice operators all over the world, with consultants from every region highlighting the shift from keg or draft beer to cans ‒ often craft beer ‒ to prevent any leftover beer going to waste.

Operators are placing more emphasis on pre- and post-game offers. In Australia, Otto Meile, national foodservice sales manager at Moffat, is seeing the variety of food on offer pre- and post-game increase. “Food vans are operating around the periphery of the venues to cater to the before and after game food and beverage requirements. The menus are becoming larger and more varied, including kebabs, donuts, coffee, pastry vans and more.”

Operators must also think about how to generate revenue beyond event days to survive throughout the year. “We’re seeing new build and renovations of stadiums often incorporate full-service restaurants and cafes that are available to the public during normal restaurant and café trading hours, bringing stadiums alive outside game times,” Meile notes.

With thousands of fans streaming through every day, stadia are ideal venues to raise awareness of a brand before launching it further afield. Heim cites retired NBA star Shaquille O’Neal’s Big Chicken brand, which started in arenas and is now launching standalone restaurants across the US. In a similar vein, some venues even have test kitchen concepts, which allow emerging brands to gain exposure among large crowds.

The sports catering equation

Making the catering a success comes down to three elements, according to Sedej: what you’re serving to how many people in what period of time. “Once you understand that equation, it needs to be married with your vision and the infrastructure and operational support you have to make it happen,” she says. “There’s no right answer; it really comes down to numbers and metrics.”

Close coordination between the parties involved in making the vision reality is key. “The person who’s generating the menu needs to talk to the person procuring the equipment. Operators also need to understand how the flow of people, food and trash works at the venue and how that matches with their labor model. Do they have enough people to accomplish what they’re trying to do? The design piece – the tools in the toolbox as I call it – are crucial but it’s the operators and staff that make the magic happen. It’s about asking the right questions and getting the right people to the table to answer those questions.”

As event organizers brace themselves to raise the curtain on an exciting summer of sport, we can only hope that those questions have already been asked and answered. Let the games begin.

Elly Earls